Published 2024-11-08

Keywords

- Hostile Sexism,

- Gender,

- Voting Choice,

- Political Orientation,

- Candidate Evaluation

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2024 Mauro Bertolotti, Laura Picciafoco, Patrizia Catellani

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

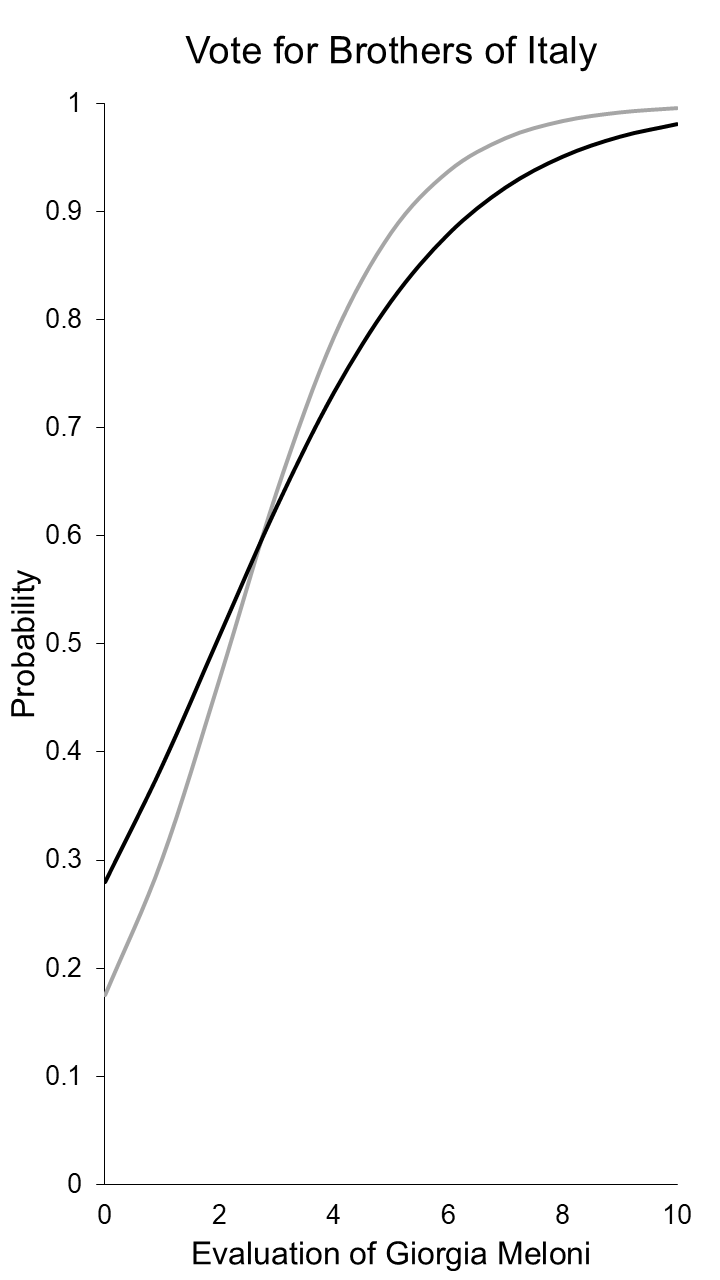

We examined the role of hostile sexism in vote at the 2022 general election in Italy, where the largest among center-right parties was led by a woman, Giorgia Meloni. We analyzed data from a sample of 1635 voters who participated in the 2022 ITANES survey. Hostile sexism was associated with male gender, lower education, higher religiosity, and right-wing orientation. As to vote choice, hostile sexism was positively associated with vote for Brothers of Italy and the other center-right parties. However, such association was significantly moderated by the evaluation of Giorgia Meloni, and disappeared among voters with a positive evaluation of her. Discussion focusses on the interplay between gender-related attitudes and candidate-based heuristics in vote choice.

References

- Bashevkin, S. (1996). Tough times in review: The British women's movement during the Thatcher years. Comparative Political Studies, 28(4), 525-552.

- Becker, J. C., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Sexism. In T.D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (pp. 407-430). Psychology Press.

- Bertolotti, M., Catellani, P., Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2013). The “Big Two” in political communication: The effects of attacking and defending politicians’ leadership and morality in two European countries. Social Psychology, 44(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000141

- Bertolotti, M., & Catellani, P. (2021). Hindsight bias and electoral outcomes: Satisfaction counts more than winner-loser status. Social Cognition, 39(2), 201-224. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2021.39.2.201

- Bock, J., Byrd-Craven, J., & Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 189-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026

- Bruckmüller, S., & Methner, N. (2018). The “Big Two” in citizens’ perceptions of politicians. In A. Abele & B. Wojciszke (Eds.) Agency and communion in social psychology (pp. 154-166). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Burns, N., & Gallagher, K. (2010). Public opinion on gender issues: The politics of equity and roles. Annual Review of Political Science, 13, 425-443.

- Cassese, E. C., & Barnes, T. D. (2019). Reconciling sexism and women’s support for Republican candidates: A look at gender, class, and whiteness in the 2012 and 2016 presidential races. Political Behavior, 41, 677-700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9468-2

- Cassese, E. C., & Holman, M. R. (2019). Playing the woman card: Ambivalent sexism in the 2016 US presidential race. Political Psychology, 40(1), 55-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12492

- Catellani, P., & Alberici, A. I. (2012). Does the candidate matter? Comparing the voting choice of early and late deciders. Political Psychology, 33(5), 619-634.

- Catellani, P., & Bertolotti, M. (2014). The effects of counterfactual attacks on social judgments. Social Psychology, 45(5), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1995

- Cavazza, N., & Roccato, M. (2024). When a woman asks to be voted to a sexist constituency: was Giorgia Meloni’s gender an advantage, a disadvantage or an irrelevant factor in the 2022 Italian general election?. Italian Journal of Electoral Studies (IJES), 87(1). https://doi.org/10.36253/qoe-14090

- Celis, K., & Childs, S. (2018). Conservatism and Women's Political Representation. Politics & Gender, 14(1), 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X17000575

- Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 223-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00284.

- Coffé, H. (2018). Gender and the radical right. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right (pp. 200-211). Oxford University Press.

- Coffé, H., & von Schoultz, Å. (2021). How candidate characteristics matter: Candidate profiles, political sophistication, and vote choice. Politics, 41(2), 137-155.

- De Geus, R., Ralph-Morrow, E., & Shorrocks, R. (2022). Understanding ambivalent sexism and its relationship with electoral choice in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 1564-1583. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000612

- Ditonto, T. (2019). Direct and indirect effects of prejudice: Sexism, information, and voting behavior in political campaigns. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(3), 590-609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2019.1632065

- Edwards, M., & Schaffner, B. (2020). Sexism among American adults. Contexts, 19(4), 72-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220977942

- Everitt, J., & Horvath, L. (2021) Public Attitudes and Private Prejudices: Assessing Voters’ Willingness to Vote for Out Lesbian and Gay Candidates. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 662095.

- Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207(4), 93-106.

- Frye, M. (1983). Sexism. In M. Frye (Ed.), The politics of reality: Essays in feminist theory (pp. 17-40). Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

- Gaweda, B., Siddi, M., & Miller, C. (2022). What’s in a name? Gender equality and the European Conservatives and Reformists’ group in the European Parliament. Party Politics, 29(5), 829-839. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221116247.

- Garzia, D., & De Angelis, A. (2016). Partisanship, leader evaluations and the vote: Disentangling the new iron triangle in electoral research. Comparative European Politics, 14, 604-625.

- Glick, P. (2019). Gender, sexism, and the election: Did sexism help Trump more than it hurt Clinton? Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(3), 713-723. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2019.1633931

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

- Golec de Zavala, A., & Bierwiaczonek, K. (2021). Male, national, and religious collective narcissism predict sexism. Sex Roles, 84(11-12), 680-700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01193-3

- Gray, M. M., Kittilson, M. C., & Sandholtz, W. (2006). Women and globalization: A study of 180 countries, 1975–2000. International organization, 60(2), 293-333. https://doi.org 10.1017/S0020818306060176

- Hall, C. C., Goren, A., Chaiken, S., & Todorov, A. (2009). Shallow cues with deep effects: Trait judgments from faces and voting decisions. In E. Bordiga, C. M. Federico, & J. L. Sullivan (Eds.), The political psychology of democratic citizenship (pp. 73–99). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge University Press.

- Kidd, Q., Diggs, H., Farooq, M., & Murray, M. (2007). Black voters, black candidates, and social issues: Does party identification matter? Social Science Quarterly, 88(1), 165-176.

- Kittilson, M. C., & Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2012). The gendered effects of electoral institutions: Political engagement and participation. Oxford University Press.

- Köttig, M., Bitzan, R., & Petö, A. (Eds.). (2017). Gender and far right politics in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Krook, M. L. (2006). Reforming representation: The diffusion of candidate gender quotas worldwide. Politics & Gender, 2(3), 303-327. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X06060107

- Legnante, G., & Regalia, M. (2020). Gender quotas in the 2019 European elections: insights from the Italian case. Contemporary Italian Politics, 12(3), 350-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2020.1780032

- López-Sáez, M. Á., García-Dauder, D., & Montero, I. (2020). Intersections around ambivalent sexism: internalized homonegativity, resistance to heteronormativity and other correlates. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 608793. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608793

- Lovenduski, J. (2010). The dynamics of gender and party. In M.L. Krooks, & S. Childs (Eds.), Women, Gender, and Politics: A reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Manganelli Rattazzi, A. M., Volpato, C., & Canova, L. (2008). L'atteggiamento ambivalente verso donne e uomini. Un contributo alla validazione delle scale ASI e AMI. Giornale italiano di psicologia, 35(1), 217-246. https://doi.org/10.1421/26601

- Mushaben, J. M. (2017). Becoming Madam Chancellor: Angela Merkel and the Berlin Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250

- Ponton, D. M. (2010). The female political leader: A study of gender-identity in the case of Margaret Thatcher. Journal of Language and Politics, 9(2),, 195-218. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.9.2.02pon

- Ratliff, K. A., Redford, L., Conway, J., & Smith, C. T. (2019). Engendering support: Hostile sexism predicts voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(4), 578-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217741203

- Sampugnaro, R., & Montemagno, F. (2020). Women and the Italian general election of 2018: selection, constraints and resources in the definition of candidate profiles. Contemporary Italian Politics, 12(3), 329-349. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2020.1789338

- Schaffner, B.F., MacWilliams, M., & Nteta, T. (2018). Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: The sobering role of racism and sexism. Political Science Quarterly, 133(1), 9 –34. https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.12737

- Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Political Psychology, 40, S1, 173-213. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12573

- Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Duckitt, J. (2007). Antecedents of men’s hostile and benevolent sexism: The dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 160-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206294745

- Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., & Bobo, L. (1994). Social dominance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 998. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.998

- Swim, J. K., & Hyers, L. L. (2009). Sexism. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. New York: Psychology Press.

- Van der Brug, W., & Mughan, A. (2007). Charisma, leader effects and support for right-wing populist parties. Party Politics, 13, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068806071260

- Weeks, A. C., Meguid, B. M., Kittilson, M. C., & Coffé, H. (2023). When do Männerparteien elect women? Radical right populist parties and strategic descriptive representation. American Political Science Review, 117(2), 421-438. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000107

- Winter, N. J. (2023). Hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and American elections. Politics & Gender, 19(2), 427-456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000010