Published 2024-09-07

Keywords

- Italian Elections,

- Populist Radical Right,

- Voting,

- Populism,

- Economic Dissatisfaction

- Abstentionism ...More

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2024 Giacomo Salvarani, Fabio Bordignon, Luigi Ceccarini

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

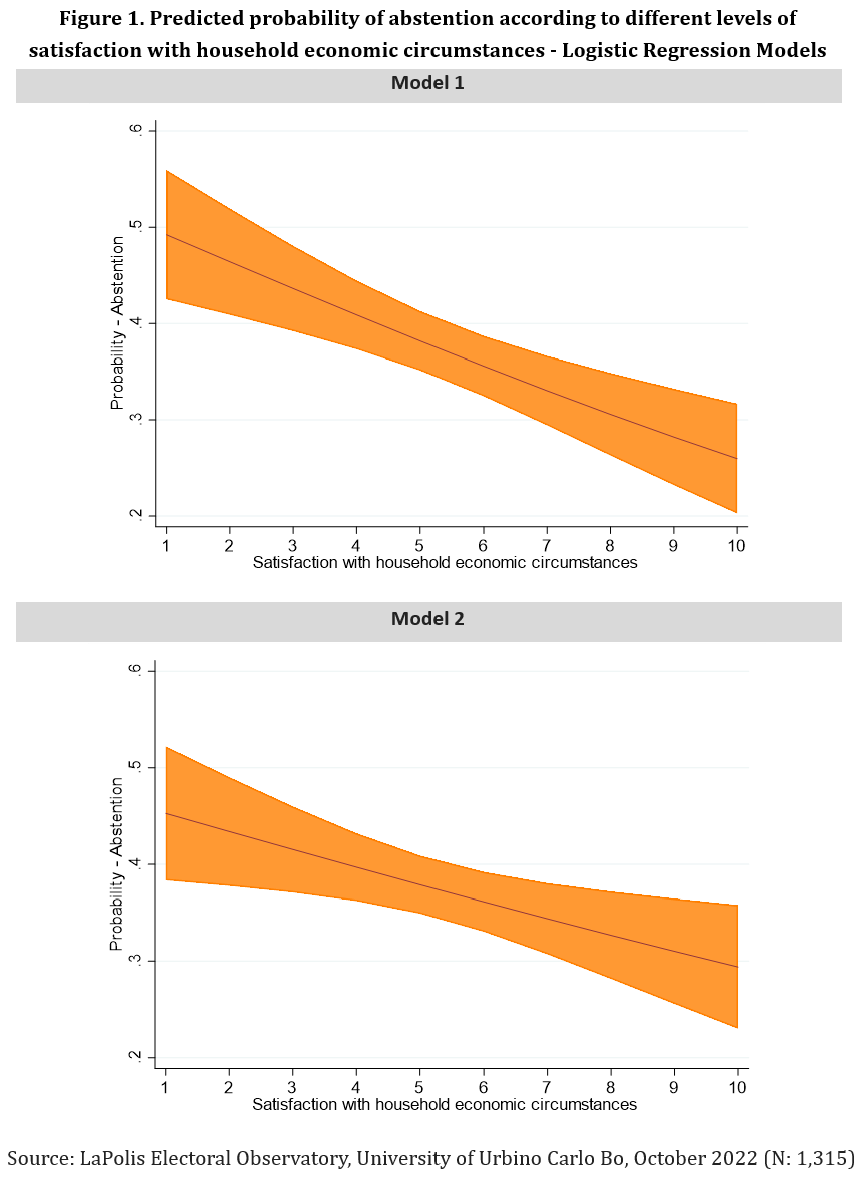

A right-wing coalition led by Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy (FdI) emerged as the clear winner of the 2022 Italian general election, with voter turnout reaching its lowest level in the history of the Italian Republic. This result unfolded amidst a long-standing sense of economic stagnation, escalating inequality, and rising inflation. The article explores the relationship between individual economic insecurity and the 2022 election results. There is an assumption in both public and scholarly discourse that economic insecurity is responsible for the rise of populist and, particularly, populist radical-right (PRR) parties. Does the 2022 Italian general election represent a case of mobilization or withdrawal of the economically insecure electorate? Building on the literature on populist success and the economy’s effects on political behavior, we find that economic insecurity was not behind the success of the PRR parties (the League and FdI) in the 2022 election. It was also not associated with the vote for the main populist non-radical-right party in the Italian political landscape: the 5-Star Movement. On the contrary, in this election, economic insecurity mostly deterred voters from casting their ballots, and the success of the PRR can mostly be explained by anti-immigration attitudes.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T., & Kayser, M. A. (2017). It’s not easy being green: Why voters punish parties for environmental policies during economic downturns. Electoral Studies, 45, 201-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.10.009.

- Angelucci, D., & De Sio, L. (2021). Issue characterization of electoral change (and how recent elections in Western Europe were won on economic issues). Quaderni dell'Osservatorio Elettorale QOE - IJES, 84(1), 45-67. https://doi.org/10.36253/qoe-10836.

- Antonucci, L., D’Ippoliti, C., Horvath, L., & Krouwel, A. (2023). What’s work got to do with it? How precarity influences radical party support in France and the Netherlands. Sociological Research Online, 28(1), 110-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/13607804211020321.

- Azzollini, L. (2021). The scar effects of unemployment on electoral participation: Withdrawal and mobilization across European societies. European Sociological Review, 37(6), 1007-1026. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab016.

- Bellucci, P. (2023). Il governo Draghi, l’economia e il voto retrospettivo. In ITANES, Svolta a destra? Cosa ci dice il voto del 2022. Il Mulino.

- Betz, H.-G., & Immerfall, S. (1998). The new politics of the right: Neo-populist parties and movements in established democracies. St. Martin’s Press.

- Blais, A., & Daoust, J.-F. (2020). The motivation to vote. UBC Press.

- Bloise, F., Chironi, D., Della Porta, D., & Pianta, M. (2023). Inequality and elections in Italy, 1994–2018. Italian Economic Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-022-00218-y.

- Bordignon, F., & Ceccarini, L. (2018). Towards the 5 star party. Contemporary Italian Politics, 10(4), 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2018. 1544351.

- Bordignon, F., & Salvarani, G. (2023). Outside the Ballot Box: Who Is the Italian Abstainer?. In Bordignon, F., Ceccarini, L., Newell, J.L. (Eds.), Italy at the Polls 2022. The Right Strikes Back. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29298-9_6.

- Bossert, W., Clark, A., D’Ambrosio, C., & Lepinteur, A. (2023). Economic insecurity and political preferences. Oxford Economic Papers, 75(3), 802-825. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpac037.

- Burden, B. C., & Wichowsky, A. (2014). Economic discontent as a mobilizer: Unemployment and voter turnout. The Journal of Politics, 76(4), 887-898. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000437.

- Colloca, P., Maggini, N., & Valbruzzi, M. (2021). Periferie urbane e disagio socio-economico: com’è cambiato il voto degli italiani tra il 2008 e il 2018, in Valbruzzi, M. (ed.), Come votano le periferie? Comportamento elettorale e disagio sociale nelle città italiane. Il Mulino.

- Caciagli, M. (2011). Subculture politiche territoriali o geografia elettorale?. SocietàMutamentoPolitica, 2(3), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.13128/SMP-10320.

- Caiani, M., & Padoan, E. (2021). Populism and the (Italian) crisis: The voters and the context. Politics, 41(3), 334-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720952627.

- Ceccarini, L. (2018). Un nuovo cleavage? I perdenti e i vincenti della globalizzazione, in Bordignon, F., Ceccarini, L., & Diamanti, I. (eds.). Le divergenze parallele. L'Italia: dal voto devoto al voto liquido. Laterza.

- Cetrulo, A., Lanini, M., Sbardella, A., & Virgillito, M. E. (2023). Non-Voting Party and Wage Inequalities: Long-Term Evidence from Italy. Intereconomics, 58(4), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.2478/ie-2023-0044.

- Coffé, H., Heyndels, B., & Vermeir, J. (2007). Fertile grounds for extreme right-wing parties: Explaining the Vlaams Blok’s electoral success. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 142-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.01.005.

- Dassonneville, R., Feitosa, F., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2022). Economics and Political Participation. In M. Giugni & M. Grasso (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation (1st ed., pp. 83–100). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198861126.013.2.

- De Sio, L., & Paparo, A. (2023). Tra vittoria del centrodestra e M5s più che dimezzato: l’analisi dei flussi elettorali. In ITANES, Svolta a destra? Cosa ci dice il voto del 2022. Il Mulino.

- Diamanti, I. (2013). Un salto nel voto: ritratto politico dell'Italia di oggi. Gius. Laterza & Figli Spa.

- Duch, R. M., & Stevenson, R. T. (2008). The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511755934.

- Engler, S., & Weisstanner, D. (2021). The threat of social decline: Income inequality and radical right support. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 153-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636.

- Emanuele, V., & Paparo, A. (2018). Gli sfidanti al governo. Disincanto, nuovi conflitti e diverse strategie dietro il voto del 4 marzo 2018. DOSSIER CISE, (11), 1-301.

- Franzini, F. (2022). Disuguaglianza economica, comportamenti elettorali e disuguaglianza politica, in Fumagalli, C. & Ottonelli, V. (ed.), Votare o no. La pratica democratica del voto, tra diritto individuale e scelta collettiva. Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

- Georgiadou, V., Rori, L., & Roumanias, C. (2018). Mapping the European far right in the 21st century: A meso-level analysis. Electoral Studies, 54, 103-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.05.004.

- Gidron, N., & Mijs, J. J. B. (2019). Do changes in material circumstances drive support for populist radical parties? Panel data evidence from the Netherlands during the Great Recession, 2007–2015. European Sociological Review, 35(5), 637-650. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz023.

- Giuliani, M. (2023). Did the citizenship income scheme do it? The supposed electoral consequence of a flagship policy. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.19.

- Guiso, L., Herrera, H., Morelli, M., & Sonno, T. (2024). Economic insecurity and the demand for populism in Europe. Economica, 91(362), 588–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12513.

- Han, K. J. (2016). Income inequality and voting for radical right-wing parties. Electoral Studies, 42, 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.001.

- Heath, O. (2018). Policy alienation, social alienation and working-class abstention in Britain, 1964–2010. British Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 1053-1073.

- Helgason, A. F., & Mérola, V. (2017). Employment insecurity, incumbent partisanship, and voting behavior in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 50(11), 1489-1523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016679176.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1972). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

- King, B. G., & Carberry, E. J. (2022). Political Participation and the Economy. In M. Giugni & M. Grasso (A c. Di), The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation (1a ed., pp. 523–542). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198861126.013.31.

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887879.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790720.

- Lahtinen, H., Mattila, M., Wass, H., & Martikainen, P. (2017). Explaining social class inequality in voter turnout: The contribution of income and health. Scandinavian Political Studies, 40(4), 388-410.

- Lucassen, G., & Lubbers, M. (2012). Who fears what? Explaining far-right-wing preference in Europe by distinguishing perceived cultural and economic ethnic threats. Comparative Political Studies, 45(5), 547-574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011427851.

- Maggini, N., & Vezzoni, C. (2023). Competizione e spazio elettorale nelle elezioni del 2022. In ITANES, Svolta a destra? Cosa ci dice il voto del 2022. Il Mulino.

- Margalit, Y. (2019). Economic insecurity and the causes of populism, reconsidered. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 152-170. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.152.

- Mete, V. (2022). Anti-politics in contemporary Italy. Routledge.

- Morlino, L., & Raniolo, F. (2017). The Impact of the Economic Crisis on South European Democracies. Springer International Publishing.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147-174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11.

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash (HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2818659.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108595841.

- Oesch, D., & Rennwald, L. (2018). Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, center-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 783-807. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12259.

- Passarelli, G., & Tuorto, D. (2014). Not with my vote: Turnout and the economic crisis in Italy. Contemporary Italian Politics, 6(2), 147-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2014.924232.

- Rebechi, A., & Rohde, N. (2022). Economic insecurity, racial anxiety, and right-wing populism. Review of Income and Wealth. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12599.

- Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L. P., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Kessel, S. V., Lange, S. L. D., ... Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList: A database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties using expert-informed qualitative comparative classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431.

- Plaza-Colodro, C., & Lisi, M. (2024). Between exit and voice. Differential factors of abstentionists and populist voters in Portugal. Análise Social, e22119 Páginas. https://doi.org/10.31447/2022119.

- Scheiring, G., Serrano-Alarcón, M., Moise, A., McNamara, C., & Stuckler, D. (2024). The Populist Backlash Against Globalization: A Meta-Analysis of the Causal Evidence. British Journal of Political Science, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000024.

- Schlozman, K., Brady, H., & Verba, S. (2018). Unequal and unrepresented: Political inequality and the people's voice in the new gilded age. Princeton University Press.

- Sipma, T., Lubbers, M., & Spierings, N. (2023). Working-class economic insecurity and voting for radical right and radical left parties. Social Science Research, 109, 102778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2022.102778.

- Stoetzer, L. F., Giesecke, J., & Klüver, H. (2023). How does income inequality affect the support for populist parties? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1981981.

- Tuorto, D. (2018). I non rappresentati. La galassia dell’astensione prima e dopo il voto del 2018. Teoria politica, 8, 263-273.

- Tuorto, D. (2023). Disuguaglianze socioeconomiche ed esclusione elettorale: il caso italiano in prospettiva comparata. Etica pubblica: studi su legalità e partecipazione: 2, 35-55.

- Watson, B., Law, S., & Osberg, L. (2022). Are populists insecure about themselves or about their country? Political attitudes and economic perceptions. Social Indicators Research, 159(2), 667-705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02767-8.

- Zulianello, M., & Larsen, E. G. (2021). Populist Parties in European Parliament Elections: A New Dataset on Left, Right and Valence Populism from 1979 to 2019. Electoral studies, 71. 102312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102312.