This is not US: measuring polarization in multiparty systems. A quasi-replication study

Pubblicato 2024-01-01

Parole chiave

- Affective Polarization,

- Measurement,

- Methodology,

- Political Behaviour

Come citare

Copyright (c) 2023 Luana Russo, Emma Turkenburg, Eelco Harteveld, Anna Heckhausen

TQuesto lavoro è fornito con la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale.

Abstract

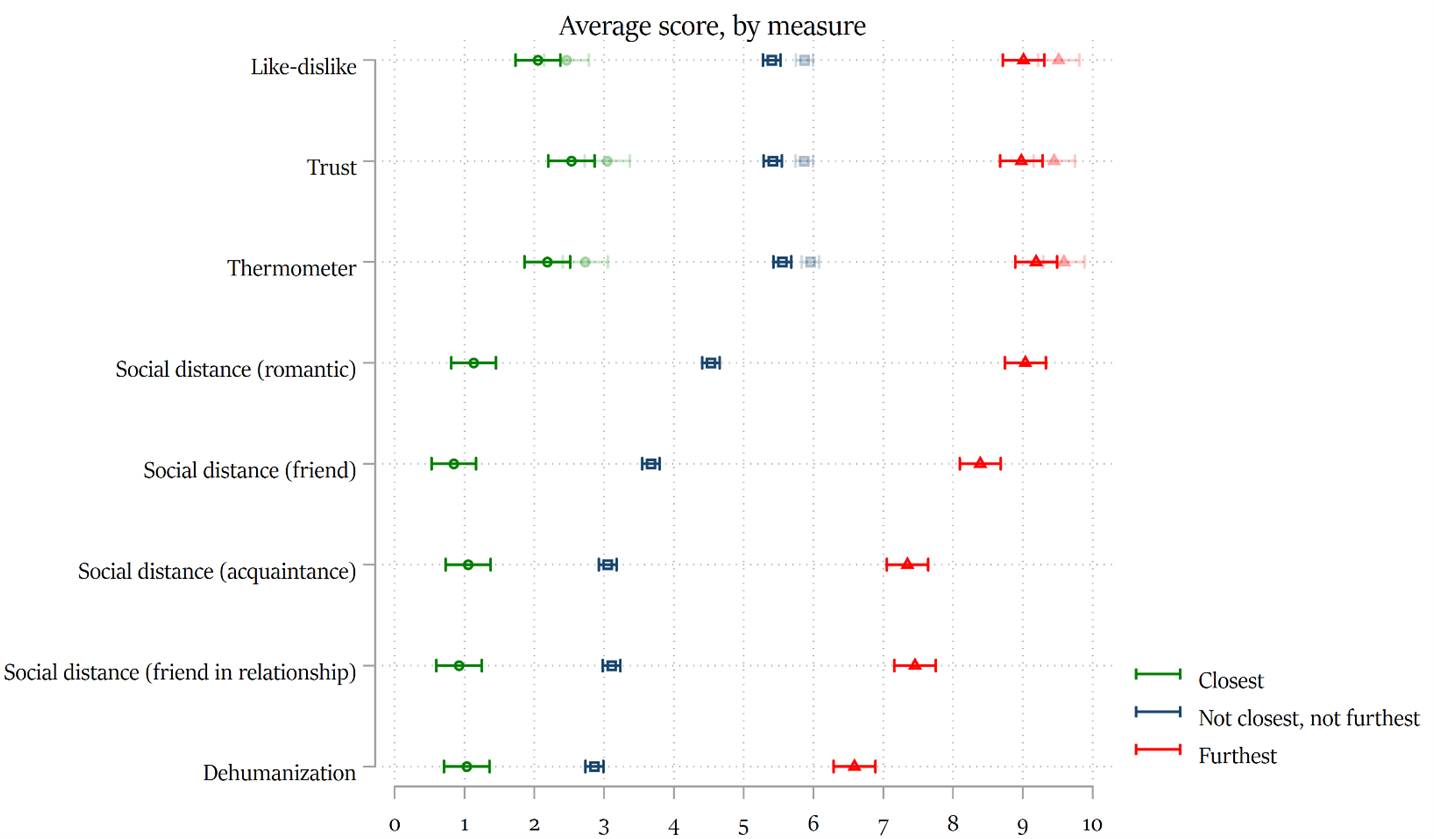

In the last decade, affective polarization (AP) has become an increasingly salient topic in both public discourse and political science. Several different measurement instruments have been developed to empirically capture this phenomenon. With the rising interest that affective polarization is now also enjoying in Europe, it has become of the utmost importance to assess what these different measures capture, and to what extent their application travels to different contexts. In this study we test several AP measures on a student population with various European nationalities. We assess their overlap and effectiveness in mapping AP, to help future research working towards greater empirical clarity, and making informed choices on which kind of measures to include in questionnaires and data collections. The results indicate that, while different items usually produce different point estimates and sometimes different answer patterns, the measurement of affective polarization appears relatively indifferent to the choice of items.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Aarøe, L. (2011). Investigating Frame Strength: The Case of Episodic and Thematic Frames. Political Communication, 29(2), 207–226.

- Achterberg, P., & Houtman, D. (2009). Ideologically illogical? Why do the lower-educated dutch display so little value coherence? Social Forces, 87(3), 1649–1670. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0164

- Almond, G. a., & Verba, S. (1963). The Civic Culture - Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations.

- Arian, A., & Shamir, M. (1983). The primrily political functions of the left-right continuum. Comparative Politics, 15(2), 139–158.

- Barisione, M. (2017). The Partisan Gap in Leader Support and Attitude Polarization in a Campaign Environment: The Cases of Germany and Italy. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 29 (4): 604–30.

- Bartle, P., & Bellucci, J. (Eds.). (2014). Political Parties and Partisanship: Social identity and individual attitudes. Routledge.

- Benz, M., & Meier, S. (2008). Do People Behave in Experiments as in the Field?: Evidence from Donations. Experimental Economics, 11, 268–81.

- Bordignon, F. (2020). Leader Polarisation: Conflict and Change in the Italian Political System. South European Society and Politics, 25 (3/4): 1–31

- Bosnjak, M., & Tuten, T. L. (2003). Prepaid and Promosied Incentives in Web Surveys – an experiment. Social Science Computer Review, 21(2), 208–2016.

- Brewer, P. R., & Gros, K. (2010). Studying the Effects of Framing on Public Opinion about Policy Issues. In D.’Angelo & J. A. R. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing News Frame Analysis Empircal and Theoretical Perspectives. New York.

- Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2018). On the Left and Right Ideological Divide: Historical Accounts and Contemporary Perspectives. Political Psychology, 39, 49–83.

- Caughey, D., O’Grady, T., & Warshaw, C. (2019). Policy Ideology in European Mass Publics, 1987 - 2016. American Political Science Review, 1–20.

- Church, A. (1993). Estimating the effect of incentives on mail survey response rates: a meta-analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57, 62–79.

- Cobanoglu, C., & Cobanoglu, N. (2003). The effect of incentives in web surveys: application and ethical considerations. International Journal of Market Research, 45(4), 475–488.

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). The Polarization of the European Party Systems – New Data , New Approach , New Results. Comparative Political Studies, 41(7).

- Druckman, J. N., Gubitz, S. R., Levendusky, M. S., & Lloyd, A. M. (2018). How Incivility On Partisan Media (De-)Polarizes the Electorate. In American Political Science Association.

- Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What Do We Measure When We Measure Affective Polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114–122.

- Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., & Ryan, J. B. (2022). (Mis) estimating affective polarization. The Journal of Politics, 84(2), 1106-1117.

- Duffy, B., Hewlet, K. irsti., McCrae, J., & Hall, J. (2019). Divided Britain? Polarisation and fragmentation trends in the UK. Sovremennaya Evropa. https://doi.org/10.2307/622618

- ESS. (2018). European Social Survey. ESS 9 Source Questionnaires.

- European Election Studies. (n.d.). The European Election Studies.

- Fayers, P. M., & Hand, D. J. (2002). CaUSl variables, indicator variables and measurement scales: An example from quality of life. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A: Statistics in Society, 165(2), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-985X.02020

- Galesic, M., & Bosnjak, M. (2009). Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(2), 349–360.

- Garrett, R. K., Dvir Gvirsman, S., Johnson, B. K., Tsfati, Y., Neo, R., & Dal, A. (2014). Human Communication Research Implications of Pro-and Counterattitudinal Information Exposure for Affective Polarization.

- Garzia, D. (2013). The Rise of Party/Leader Identification in Western Europe. Political Research Quarterly, 66(3), 533–544.

- Gong, Z., Tang ,Y., & LIU C. (2021) Can trust game measure trust?. Advances in Psychological Science: 29(1): 19-30.

- Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2018, August). How ideology, economics and institutions shape affective polarization in democratic polities. In Annual conference of the American political science association. Hansen, K. M. (2007). The Effects of Incentives, Interview Length, and Interviewer Characteristics on Response Rates in a CATI-Study. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19(1), 112–121.

- Gidron, N., Sheffer, L., & Mor, G. (2022). Validating the feeling thermometer as a measure of partisan affect in multi-party systems. Electoral Studies, 80, 102542.

- Chaiklin, H. (2011). Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Practice. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 38: Iss. 1, Article 3

- Harteveld, E. (2021). Fragmented foes : affective polarization in the multiparty context of the Netherlands. Electoral Studies, 71(October 2020), 1–22.

- Harteveld, E., Mendoza, P., & Rooduijn, M. (2021). Affective Polarization and the Populist Radical right -Creating the Hating. Government and Opposition, 1–25.

- Hawkins, K. A., Carlin, R. E., Littvay, L., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis. Routledge.

- Hogg, M. A., & Smith, J. R. (2007). Attitudes in social context: A social identity perspective. European Review of Social Psychology, 18(1).

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989.

- Iyengar, S., & Krupenkin, M. (2018). The Strengthening of Partisan Affect. Political Psychology, 39, 201–218.

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146.

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012, September). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly.

- Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and Loathing across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

- Kekkonen, A., & Ylä-Anttila, T. (2021). Affective blocs: Understanding affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 72.

- Kingzette, J. (2021). Who Do You Loathe? Feelings toward Politicians vs. Ordinary People in the Opposing Party. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 8, 75–84.

- Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., & Ryan, J. B. (2018). Affective polarization or partisan disdain? Untangling a dislike for the opposing party from a dislike of partisanship. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(2).

- Kleiner, T.-M. (2018). Public opinion polarisation and protest behaviour. European Journal of Political Research, 57, 941–962.

- Krupnikov, Y., Nam, H. H., & Style, H. (2021). Convenience Samples in Political Science Experiments. In J. Druckman & D. P. Green (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Political Science (pp. 165–183). Cambridge.: Cambridge University Press.

- Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 901–931.

- Laguilles, J. S., Williams, E. A., & Saunders, D. B. (2011). Can Lottery Incentives Boost Web Survey Response Rates? Findings from Four Experiments. Research in Higher Education, 52(5), 537–553.

- LeBas, A. (2018). Can Polarization Be Positive? Conflict and Institutional Development in Africa. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 59–74.

- Lelkes, Y. (2016). The polls-review: Mass polarization: Manifestations and measurements. Public Opinion Quarterly. Oxford University Press.

- Levendusky, M., & Malhotra, N. (2016). Does Media Coverage of Partisan Polarization Affect Political Attitudes? Political Communication, 33(2), 283–301.

- Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9094-0

- Luskin, R. C. (1987). Measuring Political Sophistication. American Journal of Political Science, 31(4), 856–899.

- Martherus, J. L., Martinez, A. G., Piff, P. K., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2019). Party Animals? Extreme Partisan Polarization and Dehumanization. Political Behavior.

- Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

- Mason, L. (2018a). Ideologues without issues: The polarizing consequences of ideological identities. J, 82(1).

- Mason, L. (2018b). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press.

- McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1).

- Merkley, E., Cutler, F., Quirk, P. J., & Nyblade, B. (2019). Having their say: Authority, voice, and satisfaction with democracy. Journal of Politics, 81(3), 848–861.

- Moore-Berg, S. L., Hameiri, B., & Bruneau, E. (2020). The prime psychological suspects of toxic political polarization. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 199–204.

- Munzert, S., & Selb, P. (2017). Measuring Political Knowledge in Web-Based Surveys: An Experimental Validation of Visual Versus Verbal Instruments. Social Science Computer Review, 35(2), 167–183.

- Ondercin, H. L., & Lizotte, M. K. (2020). You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling: How Gender Shapes Affective Polarization. American Politics Research, 49(3), 282–292.

- Oosterwaal, A., & Torenvlied, R. (2010). Politics Divided from Society? Three Explanations for Trends in Societal and Political Polarisation in the Netherlands.

- Petrocik, J. R. (2009). Measuring party support: Leaners are not independents. Electoral Studies, 28(4).

- Poole, K. T. (2011). The Roots of the Polarization of Modern US Politics. SSRN Electronic Journal, (September 2008).

- Porter, S. R., & Whitcomb, M. E. (2003). The impact of lottery incentives on student survey response rates. Research in Higher Education, 44(4), 389–407.

- Ran, W., Yamamoto, M., & Xu, S. (2016). Media multitasking during political news consumption - a relationship with factual and subjective political knowledge. Computers in HUman Behavior, 56, 352–359.

- Rapeli, L. (2014). The Conception of Citizen Knowledge in Practices of Democracy. Palgrave Pivot.

- Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines’ (also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 376–396.

- Rogowski, J. C., & Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How Ideology Fuels Affective Polarization. Political Behavior, 38, 485–508.

- Russo, L., Franklin, M. N., & Beyens, S. (2021). Clarity of voter choices: neglected foundation for ideological congruence. Quaderni Dell’Osservatorio Elettorale QOE - IJES, 83(2), 3–13.

- Sears, D. O. (1986). College Sophomores in the Laboratory: Influence of a Narrow Data Base on Social Psychology’s View of Human Nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 515–30.

- Singer, E., Hoewyk, J., & Maher, M. (2000). Experiments with incentives in telephone surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 171–188.

- Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. (2016). Thematische collectie: Culturele Veranderingen in Nederland (CV) en SCP Leefsituatie Index (SLI). Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek.

- Spoon, J. J., & Klüver, H. (2015). Voter polarisation and party responsiveness: Why parties emphasise divided issues, but remain silent on unified issues. European Journal of Political Research, 54, 343–362.

- Strabac, Z., & Aalberg, T. (2011). Measuring political knowledge in telephone and web surveys: A cross-national comparison. Social Science Computer Review, 29(2), 175–192.

- Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2).

- Thomassen, J. J. A. (1976). Party identification as a cross-national concept: Its meaning in the Netherlands. In: Party identification and beyond: Representations of voting and party competition (pp. 63–79). Wiley.

- Thomassen, J. J. A., & Rosema, M. (2009). Party identification revisited. In: Political Parties and Partisanship. Social identity and individual attitudes (pp. 42–59). Routledge. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/party-identification-revisited

- Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 69(December 2019), 102199.

- Warriner, K., Goyder, J., Gjertsen, H., Hohner, P., & McSpurren, K. (1996). Charities, no; Lotteries, no; Cash, yes. Main effects and interactions in a Canadian incentives experiment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 542–562.

- Webster, S. W., & Abramowitz, A. I. (2017). The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the US Electorate. American Politics Research, 45(4).

- Westwood, S. J., Iyengar, S., Walgrave, S., Leonisio, R., Miller, L., & Strijbis, O. (2018). The tie that divides: Cross-national evidence of the primacy of partyism. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 333–354.

- Wilcox, C., Sigelman, L., & Cook, E. (1989). Some like it hot. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(2), 246–257.