Politicization and domestication of European issues: Italian citizen engagement on social media during the 2024 European election campaign

Pubblicato 2025-09-16

Parole chiave

- Election Campaign,

- European Parliament Elections,

- Italy ,

- Party Leaders ,

- Social Media

Come citare

Copyright (c) 2025 Antonella Seddone, Giuliano Bobba, Elisa Iannone, Costanza Massidda

TQuesto lavoro è fornito con la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale.

Abstract

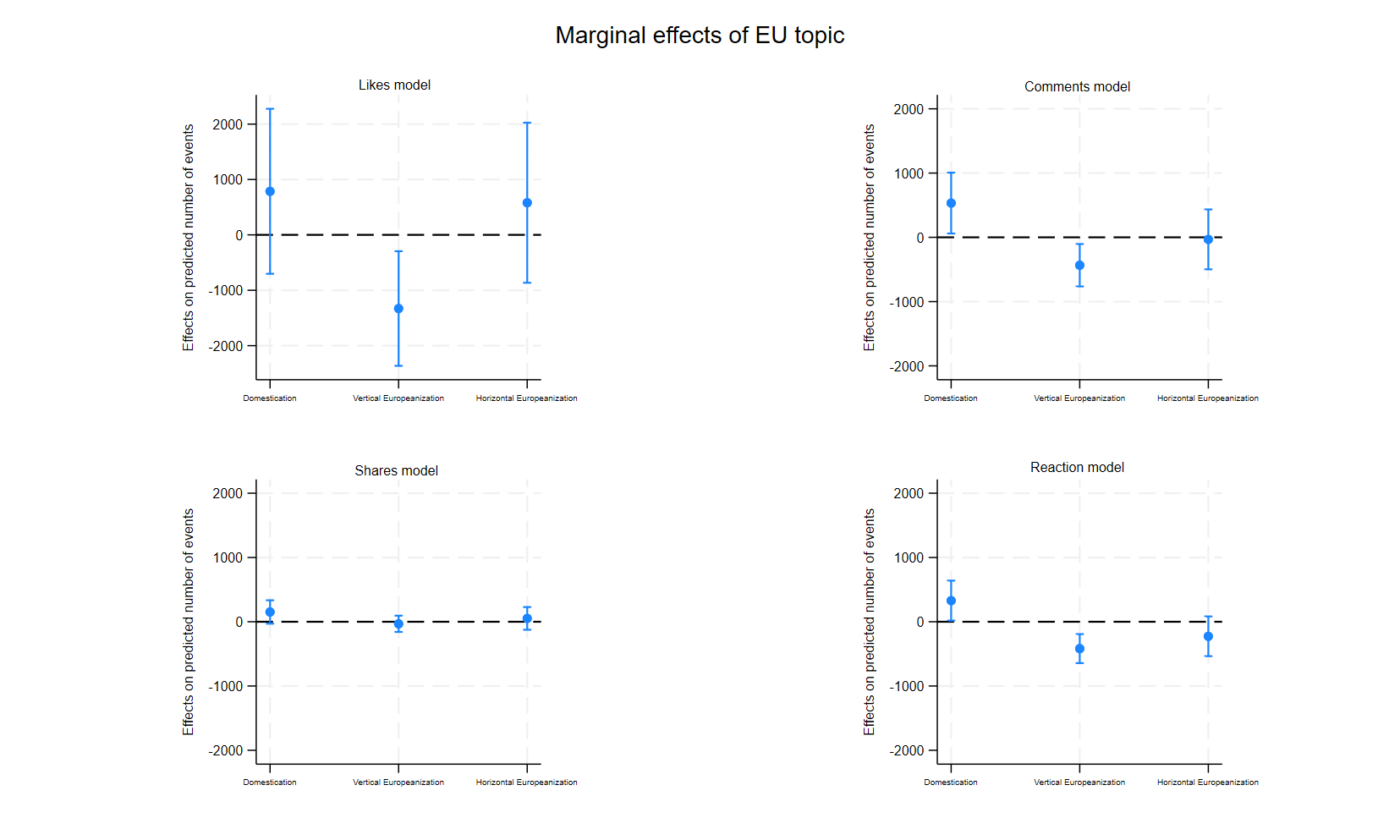

The second-order election (SOE) paradigm suggests that citizens generally perceive European elections as less important than national ones. However, recent research shows that European Union (EU) politicization has increased the salience of its institutions and policies in national political debates. This growing prominence is often accompanied by contentiousness, marked by critical and negative tones from political actors and the media. Moreover, progressive expansion of EU competencies has blurred the line between domestic and European politics, fostering the normalization and domestication of EU issues. This paper investigates how Italian citizens engaged with social media during the 2024 European Parliament election campaign. Specifically, it examines whether politicization and domestication influenced citizen engagement—measured through likes, shares, and comments. Analytically, the paper utilizes original data comprising the complete set of Facebook posts published by the leaders of the five principal Italian parties during 2024 EP elections. Our results suggest that Domestication may represent a driver for social media engagement compared to Europeanized contents. Negative sentiment is confirmed to be a factor eliciting users’ interaction with social media contents, but when applied to EU related issues the interaction produces mixed results.

Riferimenti bibliografici

- Alt, D., Brandes, E., & Nonhoff, D. (2023). First Order for some. How Different Forms of Politicization Motivated Voters in the 2019 European Parliamentary Election. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(2), 362-378.

- Bellamy, R., & Kröger, S. (2016). The politicization of European integration: National parliaments and the democratic disconnect. Comparative European Politics, 14, 125-130.

- Bene, M., Magin, M., Jackson, D., Lilleker, D., Balaban, D., Branowski, P., Haßler, J., Kruschinski, S., & Russmann, U. (2022). The Polyphonic Sounds of Europe: Users' Engagement With Parties’ European-Focused Facebook Posts. Politics and Governance, 10(1), 108–120.

- Bobba, G. (2019). Social media populism: Features and ‘likeability’ of Lega Nord communication on Facebook. European Political Science, 18(1), 11–23.

- Bobba, G., Roncarolo, F., & Seddone, A. (2025). Contestata, negoziata e addomesticata? Il processo di integrazione europea nel discorso pubblico e politico in Italia (2019 e il 2024). Fondazione Feltrinelli.

- Bobba, G., & Seddone, A. (2018). How do Eurosceptic parties and economic crisis affect news coverage of the European Union? Evidence from the 2014 European elections in Italy. European Politics and Society, 19(2), 147-165.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., & De Vreese, C. H. (2016). Do European elections create a European public sphere. In W. van der Brug & C. H. de Vreese (Eds.), 19-35.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., de Vreese, C. H., Schuck, A. R., Azrout, R., Elenbaas, M., van Spanje, J., & Vliegenthart, R. (2013). Across time and space: Explaining variation in news coverage of the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 52(5), 608–629.

- Bossetta, M., Dutceac Segesten, A., & Trenz, H. J. (2017). Engaging with European politics through Twitter and Facebook: Participation beyond the national?. In M. Barisione & A. Michailidou (Eds.) Social media and European politics: Rethinking power and legitimacy in the digital era, 53-76.

- Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S. election. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(2), 471–496.

- Braun, D., & Grande, E. (2021). Politicizing Europe in elections to the European parliament (1994–2019): the crucial role of mainstream parties. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(5), 1124-1141.

- Caiani, M., & Guerra, S. (Eds.). (2017). Euroscepticism, democracy and the media: Communicating Europe, contesting Europe. Springer.

- Conti, N., Marangoni, F., & Verzichelli, L. (2020). Euroscepticism in Italy from the Onset of the Crisis: Tired of Europe?. South European Society and Politics, 1-26.

- Cremonesi, C., Seddone, A., Bobba, G., & Mancosu, M. (2019). The European Union in the media coverage of the 2019 European election campaign in Italy: towards the Europeanization of the Italian public sphere. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 24(5), 668-6.

- Crespy, A., Moreira Ramalho, T., & Schmidt, V. (2024). Beyond ‘responsibility vs. responsiveness’: reconfigurations of EU economic governance in response to crises. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(4), 925-949.

- De Vries, C. E., & Van de Wardt, M. (2011). EU issue salience and domestic party competition. In K. Oppermann & H. Viehrig (Eds.) Issue salience in international politics, 173-187. Routledge.

- De Vreese, C. H., Banducci, S. A., Semetko, H. A., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2006). The news coverage of the 2004 European Parliamentary election campaign in 25 countries. European Union Politics, 7(4), 477–504.

- De Wilde, P., & Zürn, M. (2012). Can the politicization of European integration be reversed? Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(S1), 137–153.

- De Wilde, P., Michailidou, A., & Trenz, H. J. (2014). Converging on euroscepticism: Online polity contestation during European Parliament elections. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 766-783.

- De Wilde, P., Rasch, A., & Bossetta, M. (2022). Analyzing citizen engagement with European politics on social media. Politics and Governance, 10(1), 90–96.

- de Zúñiga, H. G. (2015). European public sphere| toward a European public sphere? The promise and perils of modern democracy in the age of digital and social media—Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 9, 3152-3160.

- Dutceac Segesten, A., & Bossetta, M. (2019a). Can Euroscepticism contribute to a European public sphere? The Europeanization of media discourses on Euroscepticism across six countries. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 1051-1070.

- Dutceac Segesten, A., & Bossetta, M. (2019b). The Eurosceptic Europeanization of public spheres: Print and social media reactions to the 2014 European Parliament elections. Comparative European Politics, 17, 361-379.

- Gattermann, K. (2013). News about the European Parliament: Patterns and drivers of broadsheet coverage. European Union Politics, 14(3), 436–457.

- Gattermann, K., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2016). Eurosceptic candidate MEPs in the news: a transnational perspective. In J. FitzGibbon,, B. Leruth & N. Startin (Eds.) Euroscepticism as a Transnational and Pan-European Phenomenon, 144-160. Routledge.

- Hänska, M., & Bauchowitz, S. (2019). Can social media facilitate a European public sphere? Transnational communication and the Europeanization of Twitter during the Eurozone crisis. Social media+ society, 5(3), 2056305119854686.

- Heidenreich, T., Eisele, O., Watanabe, K., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2022). Exploring engagement with EU news on Facebook: The influence of content characteristics. Politics and Governance, 10(1), 121-132.

- Heiss, R., Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2019). What drives interaction in political actors’ Facebook posts? Profile and content predictors of user engagement and political actors’ reactions. Information, communication & society, 22(10), 1497-1513.

- Hobolt, S. B., & De Vriese, C. E. (2016). Do European elections create a European public sphere. In W. van der Brug & C. H. de Vreese (Eds.), 19-35.

- Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2014). Blaming Europe? Responsibility without Accountability in the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe's crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996–1017.

- Jost, P., Maurer, M., & Hassler, J. (2020). Populism fuels love and anger: The impact of message features on users’ reactions on Facebook. International Journal of Communication, 14, 2081-2102.

- Kneuer, M. (2019). The tandem of populism and Euroscepticism: a comparative perspective in the light of the European crises. Contemporary Social Science, 14(1), 26-42.

- Koopmans, R., & Erbe, J. (2004). Towards a European public sphere? Vertical and horizontal dimensions of Europeanized political communication. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 17(2), 97–118.

- Koopmans, R., & Statham, P. (2002). The Making of a European Public Sphere: Media Discourse and Political Contention. Cambridge University Press.

- Lehmann, F. (2023). Talking about Europe? Explaining the salience of the European Union in the plenaries of 17 national parliaments during 2006–2019. European Union Politics, 24(2), 370-389.

- Meijers, M. (2013). The Euro-crisis as a catalyst of the Europeanization of public spheres? A cross-temporal study of the Netherlands and Germany. LEQS Paper, (62).

- Monza, S., & Anduiza, E. (2016). The visibility of the EU in the national public spheres in times of crisis and austerity. Politics & Policy, 44(3), 499-524.

- Mudde, C. (2024). The far right and the 2024 European elections. Intereconomics, 59(2), 61-65.

- Nicoli, F., van der Duin, D., Beetsma, R., Bremer, B., Burgoon, B., Kuhn, T., Meijers, M. & de Ruijter, A. (2024). Closer during crises? European identity during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(10), 3066-3092.

- Pelosi, S. (2015). SentIta and Doxa: Italian Databases and Tools for Sentiment Analysis Purposes”. In C. Bosco, S. Tonelli, & F. M. Zanzotto (Eds) Proceedings of the Second Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics CLiC-It 2015, Accademia University Press.

- Petithomme, M. (2010). Framing European integration in mediated public spheres: an increasing nationalization and contestation of European issues in party political communication?. Innovation–The European Journal of Social Science Research, 23(2), 153-168.

- Pirro, A. L., Taggart, P., & Van Kessel, S. (2018). The populist politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: Comparative conclusions. Politics, 38(3), 378-390.

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections – a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44.

- Reuters Institute (2024). Reuters Digital News Report. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024

- Risse, T. (2011). A community of Europeans?: Transnational identities and public spheres. Cornell University Press.

- Risse, T. (2015). European public spheres, the politicization of EU affairs, and its consequences. In European public spheres: Politics is back, 141-164.

- Ruiz-Soler, J. (2020). European Twitter Networks: Toward a Transnational European Public Sphere?. International Journal of Communication, 14, 5616–5642.

- Schmitt, H. (2005). The European Parliament elections of June 2004: Still second-order? West European Politics, 28(3), 650–679.

- Silva, B. C., & Proksch, S. O. (2022). Politicians unleashed? Political communication on Twitter and in parliament in Western Europe. Political science research and methods, 10(4), 776-792.

- Statham, P., & Trenz, H. J. (2012). The Politicization of Europe: Contesting the Constitution in the Mass Media. Routledge.

- Statham, P., & Trenz, H. J. (2015). Understanding the mechanisms of EU politicization: Lessons from the Eurozone crisis. Comparative European Politics, 13, 287–306.

- Trilling, D., Tolochko, P., & Burscher, B. (2016). From newsworthiness to shareworthiness: How to predict news sharing based on article characteristics. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(1), 38–60.

- Wollebæk, D., Karlsen, R., Steen-Johnsen, K., & Enjolras, B. (2019). Anger, fear, and echo chambers: The emotional basis for online behavior. Social Media+ Society, 5(2), 2056305119829859.